It's been a while since we've used two pieces from  The Wall Street Journal in one week's time, but they're on a roll lately.

The Wall Street Journal in one week's time, but they're on a roll lately.

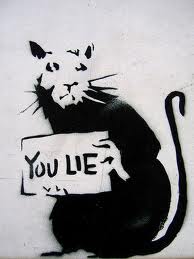

We took practically all of this piece because something is different in WSJ's linking system for this article and we found it to be very worthwhile. The link in the photo below will take you to a companion interview with WSJ writer John Hilsenrath on this group of unelected geniuses that are endeavoring mightily, while dining elegantly, to make your money worthless.

Do I seem bitter?

Inside the Risky Bets of Central Banks

BASEL, Switzerland—Every two months, more than a dozen bankers meet here on Sunday evenings to talk and dine on the 18th floor of a cylindrical building looking out on the Rhine.

The dinner discussions on money and economics are more than academic. At the table are the chiefs of the world's biggest central banks, representing countries that annually produce more than $51 trillion of gross domestic product, three-quarters of the world's economic output.

The dinner discussions on money and economics are more than academic. At the table are the chiefs of the world's biggest central banks, representing countries that annually produce more than $51 trillion of gross domestic product, three-quarters of the world's economic output.

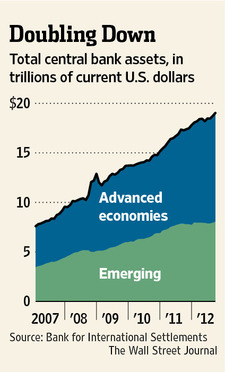

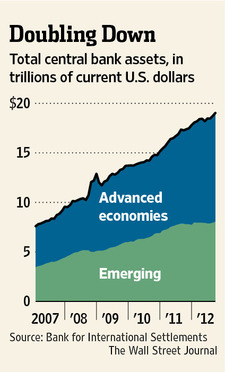

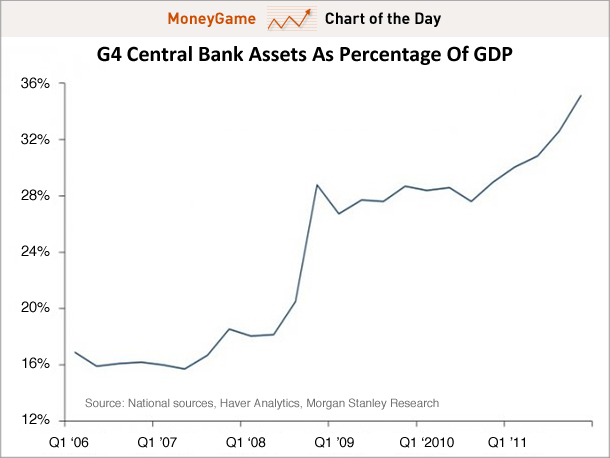

Of late, these secret talks have focused on global economic troubles and the aggressive measures by central banks to manage their national economies. Since 2007, central banks have flooded the world financial system with more than $11 trillion. Faced with weak recoveries and Europe's churning economic problems, the effort has accelerated. The biggest central banks plan to pump billions more into government bonds, mortgages and business loans.

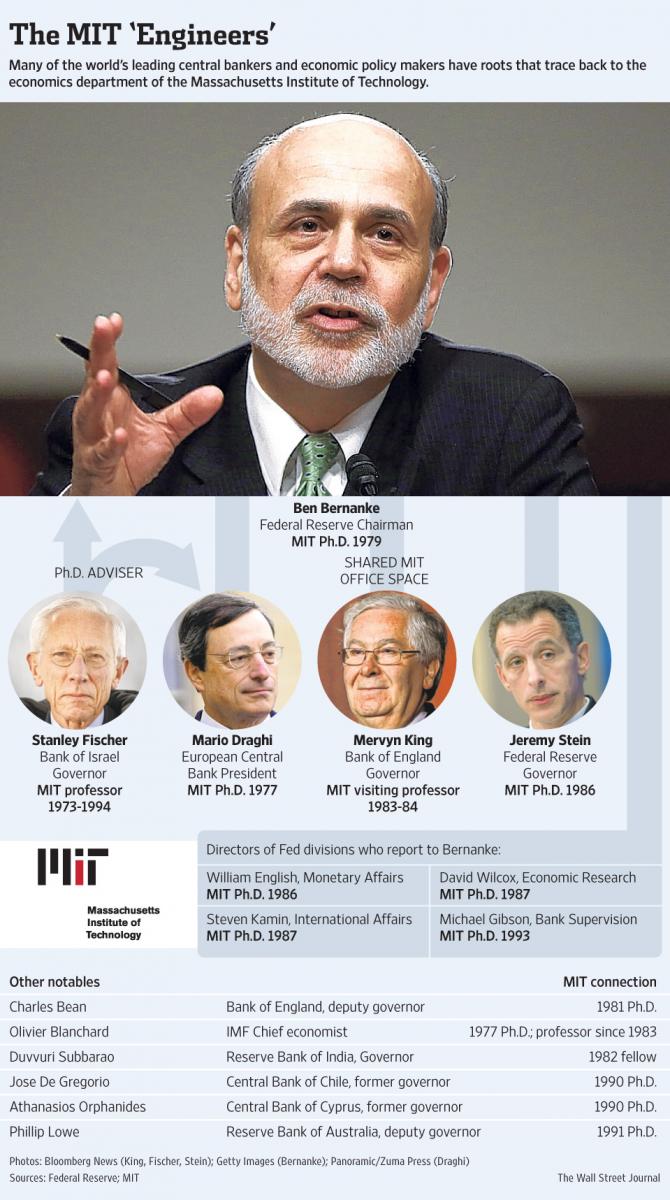

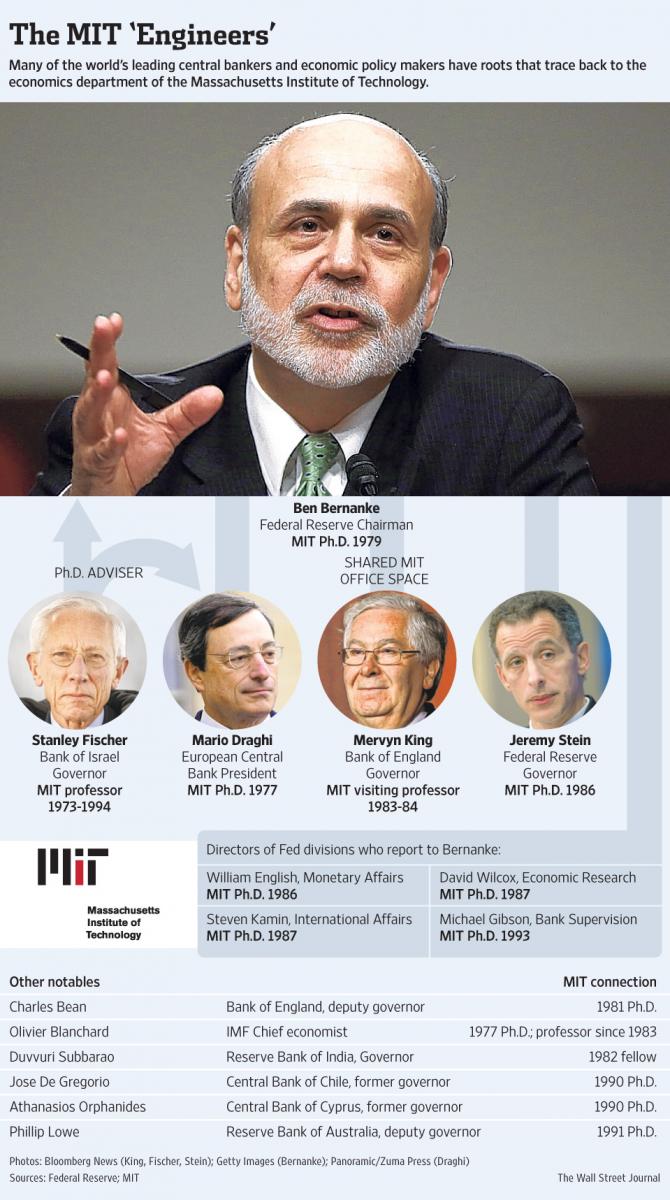

Their monetary strategy isn't found in standard textbooks. The central bankers are, in effect, conducting a high-stakes experiment, drawing in part on academic work by some of the men who studied and taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1970s and 1980s.

While many national governments, including the U.S., have failed to agree on fiscal policy—how best to balance tax revenues with spending during slow growth—the central bankers have forged their own path, independent of voters and politicians, bound by frequent conversations and relationships stretching back to university days.

The U.S. Federal Reserve now buys $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities each month and appears set at a meeting Wednesday to spend billions more on Treasury securities. The Bank of England has agreed to funnel billions of pounds to businesses and households through banks. The European Central Bank pledged to hold down borrowing costs of governments that sought help. The Bank of Japan, under increased pressure to fight deflation, is purchasing ¥91 trillion yen ($1.14 trillion) in government bonds, corporate debt and stocks.

The goal is to lower borrowing costs and stimulate stock markets to encourage spending and investment by households and business. But the method is untested on such a global scale, and central bankers have labored in behind-the-scenes meetings this year to size up the risks.

Central banks control the spigot of the world's money supply. When opened, the flow of new cash heats up economies, driving down interest rates and unemployment but risking inflation. Closing the spigot, on the other hand, raises interest rates and cools economies but tamps down prices.

The central bankers have promised that once the global economy gets back on its feet, they will shut off the spigots quickly enough to forestall inflation. But pulling back so much money, at exactly the right time, could become a political and logistical challenge.

"We're all very conscious that we're in an environment that's unusual and we're using a policy weapon that we don't have a lot of experience with," Charles Bean, deputy governor of the Bank of England said in an interview.

Central bankers themselves are among the most isolated people in government. If they confer too closely with private bankers, they risk unsettling markets or giving traders an unfair advantage. And to maintain their independence, they try to keep politicians at a distance.

Since the financial crisis erupted in late 2007, they have relied on each other for counsel. Together, they helped arrest the downward spiral of the world economy, pushing down interest rates to historic lows while pumping trillions of dollars, euros, pounds and yen into ailing banks and markets.

Three of the world's most powerful central bankers launched their careers in a building known as "E52," home to the MIT economics department. Fed ChairmanBen Bernanke and ECB President Mario Draghi earned their Ph.D.s there in the late 1970s. Bank of England Governor Mervyn King taught briefly there in the 1980s, sharing an office with Mr. Bernanke.

Many economists emerged from MIT with a belief that government could help to smooth out economic downturns. Central banks play a particularly important role in this view, not only by setting interest rates but also by influencing public expectations through carefully worded statements.

While at MIT, the central bankers dreamed up mathematical models and discussed their ideas in seminar rooms and at cheap food joints in a rundown Boston-area neighborhood on the Charles River.

Over Sunday dinners in Basel, which often stretch to three hours, they now talk of pressing, real-world problems with authority. The meals are part of two-day meetings held six times a year at the BIS. Dinner guests include leaders of the Fed, ECB, Bank of England and Bank of Japan, as well as central bankers from India, China, Mexico, Brazil and a few other countries.

The Bank of England's Mr. King leads the dinner discussions in a room decorated by the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron, which designed the "Bird's Nest" stadium for the Beijing Olympics. The men have designated seats at a round table in a dining area scented by white orchids and framed by white walls, a black ceiling and panoramic views.

"It is a way in which people can talk completely privately," Mr. King said in an interview. "It is a big advantage if you have some feel for how central banks think about questions, what they're likely to do in the future if certain events were to occur."

Serious matters follow appetizers, wine and small talk, according to people familiar with the dinners. Mr. King typically asks his colleagues to talk about the outlook in their respective countries. Others ask follow-up questions. The gatherings yield no transcripts or minutes. No staff is allowed.

The 18-member group, formally known as the Economic Consultative Committee, has only once issued a public statement: a two-line missive in September, promising to look for solutions in interbank lending markets, responding to allegations that some private banks had conspired to manipulate the Libor interest rate.

On Mondays after the dinner, the bankers join a larger group of central bankers at a large round table on a lower floor of the BIS building, which is shaped like a rook chess piece. Staff members sit nearby at desks decorated in white leather.

"These meetings are a very important forum to understand the global situation," said Duvvuri Subbarao, governor of the Reserve Bank of India and a Sunday dinner participant. "People speak freely."

"Every time there is quantitative easing by the Fed, that gets discussed," said Mr. Subbarao. "We all have to reckon with the spillover impact of our policies on other countries." Basel, he said, is the place to air such concerns.

The role of the Bank for International Settlements has broadened since it was formed in 1930 to handle reparation payments imposed on Germany after World War I. In the 1970s, it became the center of discussions on bank capital rules. In the 1990s, it became the meeting place for central bankers to talk about the global economy.

The central bankers typically stop short of formally coordinating their moves. Mr. Bernanke, Mr. Draghi and Bank of Japan head Masaaki Shirakawa are more focused on domestic challenges. Mr. Shirakawa has often warned others in Basel about the effectiveness of easy money policies, according to people familiar with his statements. That hesitance has made the BOJ an issue in Sunday's Japan elections. Shinzo Abe, the front-runner to become prime minister, has promised to rein in the BOJ's independence and demand more aggressive efforts to end consumer price deflation.

But as central bankers grapple with doubts and disagreements over reviving the global economy, they form a tightknit fraternity, tied by efforts to manage growth and gird against financial instability. Their relationships play out during conversations by phone and in person.

"A big secret of central bank cooperation," Mr. King said, "is that you can just pick up a phone and have an agreement on something very quickly" in a crisis.

This summer, the central banking clique kept in close touch as they readied for a new round of monetary activism. On June 8, Mr. Bernanke and Mr. King spoke by phone for a half-hour before policy meetings at their central banks, according to Mr. Bernanke's phone records, obtained in a public records request. A few days later, Mr. Bernanke spoke by phone with Mark Carney, head of the Bank of Canada—and last month named as Mr. King's successor. Shortly after, Mr. Bernanke called Stanley Fischer, head of the Bank of Israel, and a former MIT professor who was Mr. Bernanke's dissertation adviser.

On June 18, Mr. Bernanke had an early morning call from his home on Capitol Hill with Mr. Draghi and Mr. King, according to his phone records, as the men assessed the impact of the Greek election on Europe's financial system.

Two conflicting views tug at the world's central bankers. One view is that central banks haven't done enough to attack economic malaise. The other is that easy-money policies lack sufficient power to help economies and risk triggering runaway inflation or another financial bubble.

In August, tension over the two positions spilled into the open during the Fed's annual retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyo. Adam Posen, who recently finished a four-year term as a member of the Bank of England's monetary policy committee, chastised central bankers for their unwillingness to do more to stimulate their economies because of "self-imposed taboos."

Mr. Posen said central banks should give more help to such weakened markets as U.S. mortgages and European government bonds.

Athanasios Orphanides, another MIT professor who recently finished a term as the head of the central bank of Cyprus, took the opposing view. In the 1970s, he said, central banks sought to return unemployment to low levels of the 1960s. They made the mistake of keeping interest rates too low for too long, he said, yielding inflation instead of full employment. If banks repeat the mistake of overestimating their ability to push unemployment lower, he said, "disaster will follow on the price front."

Mr. Bean, meanwhile, said he worried that current low-interest-rate policies were losing their efficacy, an idea recently echoed by Mr. King. Low rates, he said, might induce less-than-expected business and consumer spending when governments and the private sector are burdened by too much debt.

"There is a lot we don't understand," said Donald Kohn, the Fed's former vice chairman.

Mr. Bernanke sat quietly during the discussion. But he and the other major central bankers were already primed to launch a new monetary onslaught.

A few days later, the ECB announced an agreement to buy bonds of struggling European governments in exchange for a country's adherence to fiscal austerity.

Then the Fed announced plans to buy bonds every month until U.S. job market improves "substantially." The BOJ, despite Mr. Shirakawa's hesitance, soon followed with news it also was expanding its bond-buying program.

Economists at the BIS, meanwhile, have grown more skeptical about the central bank tilt. They say their warnings of a credit bubble were ignored before the financial crisis. "Nobody took it seriously," said William White, formerly the top BIS economist.

Now, he said, the central banks may again be steering toward long-term troubles in their elusive quest for short-term growth.

Since we were already on the subject.

The dinner discussions on money and economics are more than academic. At the table are the chiefs of the world's biggest central banks, representing countries that annually produce more than $51 trillion of gross domestic product, three-quarters of the world's economic output.

The dinner discussions on money and economics are more than academic. At the table are the chiefs of the world's biggest central banks, representing countries that annually produce more than $51 trillion of gross domestic product, three-quarters of the world's economic output.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)